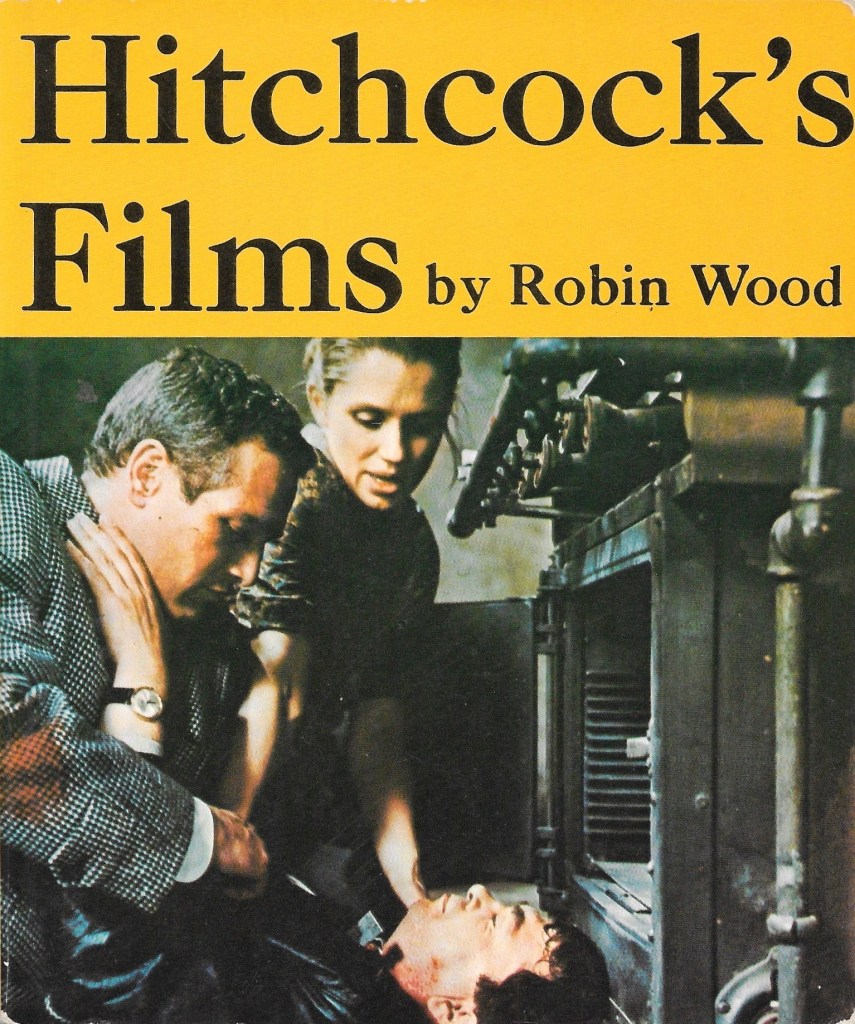

Why should we take Hitchcock seriously? Considering all of the books and documentaries about his work, the DVD and Bluray re-releases and remakes of his films, not to mention his direct influence on several generations of filmmakers, it seems like a downright silly question to ask today. But film critic and scholar Robin Wood (1931-2009) was quite earnest when that question prefaced his 1965 book Hitchcock’s Films (Tantivy Press), the first serious English-language work on the Master of Suspense, which led to both a widespread acceptance of American Film criticism and the prominence of critical director biographies.

While teaching secondary school in England, Wood began his investigation of Hitchcock’s oeuvre with an article examining the theme of sex and money in Psycho. Rejected by British film journal Sight & Sound on the grounds that Wood did not “get” that Hitchcock intended Psycho to be taken as a joke, it was eventually published by its French counterpart, Cahiers du cinéma, where Hitchcock had long been championed by its various contributors, namely Francois Truffaut, Eric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol and Jean-Luc Godard.

Wood followed this essay with his groundbreaking book, which further examined Strangers on a Train, Rear Window, Vertigo, North by Northwest, Psycho, The Birds and Marnie, and correctly predicted that they would garner ongoing critical attention in the ensuing years.

In the preface, Wood argues that, although technically and visually brilliant, Hitchcock’s American productions were populist, commercial films and when compared to the works of Ingmar Bergman and Michelangelo Antonioni, they didn’t warrant the same serious academic appreciation. But, while he criticized the Cahiers du cinéma flock for often over-analyzing and misguiding the films in order to serve a thesis, Wood used the book to champion the study of cinema as an autonomous art, worthy of the same respect given to other art forms. At the time, film criticism, especially in England, drew heavily from literary criticism and not the relatively new language of cinema. But Wood emphasized the need for examination on a visual level, not just on plot and performance — these weren’t stage plays, after all.

For instance, he describes the scene in Psycho where Norman Bates carries his mother’s limp body to the cellar. On the page, there is nothing exceptional about the scene, but cinematically, the way the camera looks down upon Norman, it enables the viewer’s understanding of the characters by plunging them into a sense of what Wood referred to as “metaphysical vertigo,” sinking deeper into darkness.

Unlike so much dry academic drivel, Wood’s prose was witty and provided rich descriptions. With Psycho, he boldly called the shower scene one of the most horrific incidents in a feature film, not because of its graphic nature, but due to its utter meaningless. He pointed out how the viewer had so far identified with Marion Crane, but her death left the film devoid of a protagonist (even though she had stolen the money, Marion sought salvation, says Wood). The film, and sense of guilt, now shifts to Norman, and here too a sort of sympathy emerges, what Wood referred to as a likeable human being in an intolerable situation.

Wood used Hitchcock’s Films as a springboard to explore other horror works throughout the 1970s. While a professor at Toronto’s York University, he co-wrote — along with his partner, Richard Lippe — The American Nightmare: Essays on the Horror Film (Festival of Festivals, 1979), the first academic look at American genre cinema, linking repression, conflict and the reactionary wing of the 20th century to to celluloid nightmares of the screen. In it, he championed the works of Brian De Palma, George A. Romero (he later hailed Day of the Dead as a brilliant satire of masculinity run amok in the Reagan era), as well as Larry Cohen — at a time when (De Palma excepted) these filmmakers received very little positive critical or box office attention.

Wood’s frank examination of Hitchcock’s career also opened the doors to other works — such as Donald Spoto’s The Art of Alfred Hitchcock (1974), which took on the slightly more ambitious task of analyzing all of Hitchcock’s films — as well as the multitudes of other books and genre publications on the director that followed.

This article was originally published in Rue Morgue Magazine #126.