Starring Boris Karloff, Ricardo Cortez, Edmund Gwenn and Marguerite Churchill / Directed by Michael Curtiz / Written by Robert Adams and Ewert Adamson

Warner Brothers. films of the 1930s were known for their stark realism, glamourizing the anti-hero and the downtrodden. The studio dominated the gangster genre, and even its musicals, while still full of glitz and glamour, featured Depression-era chorus girls waiting for their big break. Throughout that decade Warner also released a number of horror films. Michael Curtiz, one of the company’s most prolific directors (who made The Mystery of the Wax Museum and Dr. X), did something different in 1936 when he merged gangsters with the supernatural in The Walking Dead.

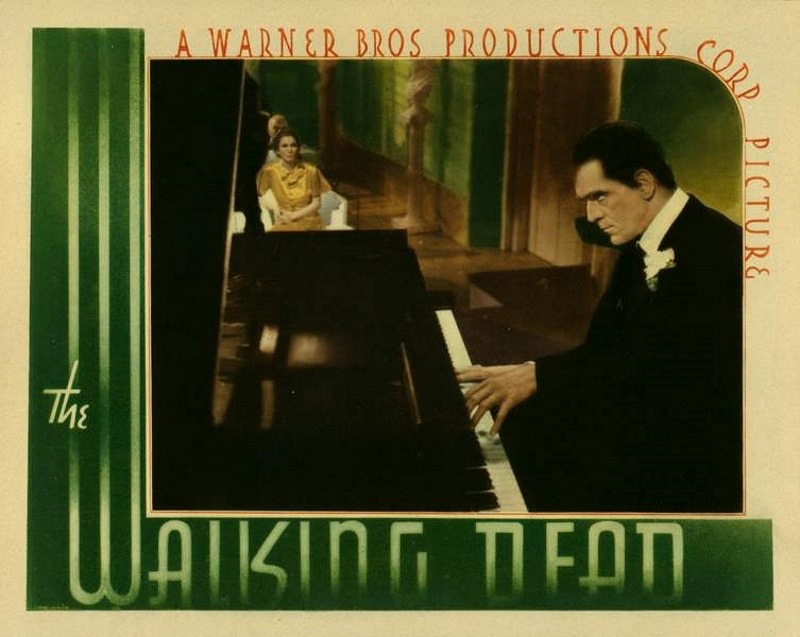

The film features Boris Karloff as John Ellman, newly freed from prison for a murder he didn’t commit. When we first see the character, he’s wearing a run-down flat-brimmed fedora and appears utterly lost in his overcoat. When he’s turned down for a job, the tone of his voice mixes desperation with pride as he announces he is a pianist – “and a good one, at that!”

Ellman’s luck only gets worse, though. When a mobster is convicted of murder, his boss, Nolan (Ricardo Cortez), seeks revenge on the judge. The gangsters frame Ellman, since the same judge had sent him away ten years earlier. When the judge’s body is found in Ellman’s car, he’s arrested and sentenced to death. Maintaining his innocence until the very end, his final words, “He’ll believe me,” are the first in a series of religious references heard throughout the film.

After the execution, a trio of scientists – two of whom witnessed the set-up – acquire Ellman’s body and revive him. Stripped of his personality, but now sporting a stylish white streak in his hair, he lumbers around Beaumont’s home like a lobotomy victim.

The similarities to Frankenstein are everywhere. When Ellman is revived, Beaumont whispers “He’s alive!” Later on, Karloff walks in as the doctor’s assistant plays the piano. He hunches towards her, not unlike the way the Monster approached Mae Clarke in James Whale’s film. However, one of the major discrepancies is that in Frankenstein, Henry is persecuted for toying with nature; here, there is no such moralistic undertone. In fact, Beaumont is lauded internationally and Ellman becomes a minor celebrity.

Ellman wasn’t privy to the set-up before his execution but learns of his fate through some divine intervention after sitting at the piano to play the song overheard at his execution. The doctors, now realizing he was framed, invite the hoodlums over for a recital. In a sequence that is half King Kong, half Tell-Tale Heart, Ellman’s eyes well up as he plays, his icy stare bringing a cold sweat to the brow of each guilty party. Converging outside, the bad guys decide to kill him again.

It’s never clear whether or not Ellman wants revenge for the wrongdoing, but he seeks out the mobsters, waxing poetically, “You can’t use that gun. You can’t escape what you’ve done.” Ellman’s constant presence as a victim may have avoided complications from the censors at the Production Code, and it works wonderfully, keeping him free of sin in a film laden with Christian overtones, yet is still spooky enough to remain in the genre.

While famous for his horror roles, Karloff was no stranger to gangster pictures, having played a heavy in Scarface and The Criminal Code, among others. Here, unencumbered by the makeup he wore in Universal’s monster films, the actor’s pleading expressions take viewers on an emotional roller coaster ride. Curtiz capitalized on this with bold close-ups and P.O.V. shots of Karloff’s gaunt appearance. As a result, the filmmaker got one of Karloff’s most tragic and under-rated performances — and it might just be the best piano-playing zombie movie ever made.

Originally published in Rue Morgue Magazine, sometime in… I dunno, 2009-2010?