Every generation of horror film fans has a coming-of-age story. Depending on how old you are, you might remember the day your dad brought a VCR into the living room, and how soon are you would spend your weekends scanning the horror sections of early 1980s video stores, all while carrying the rental tag for Escape to Witch Mountain because — let’s face it — your parents weren’t going to let you see The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

In this era of immediate accessibility to media, it’s important to remember that before the 1980s you couldn’t just stream a movie or head to the video store and buy or rent a copy of the film you wanted to see.

“The concept of watching movies at home, anytime you wanted to, seemed like something H.G. Wells dreamed up,” says Ted Okuda in his forward to Scott MacGillivray’s book Castle Films: A Hobbyist’s Guide.

Before the advent of home video, you had three options: 1) You could hope your local cinema would screen a favourite film of yours. 2) You could scan the TV Guide and hope The Ghost of Frankenstein would play on the late show. 3) If your family had an 8mm projector, you could pool your paper route money and get your mitts on a Castle Film. Offered in 8mm and later Super 8 and 16mm, these reels were an integral part of the pre-VHS home movie market.

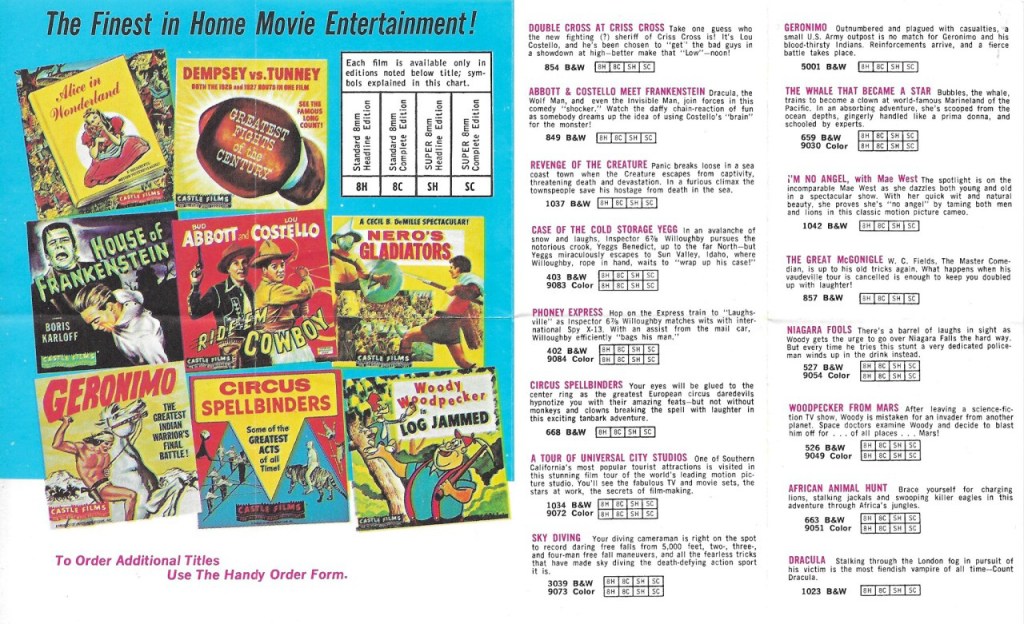

Castle started out in the 1930s by offering newsreels, cartoons, travelogues and sports subjects, then began selling abridged versions of Hollywood productions after a merger with Universal in the 1940s. They achieved great success with their digests of films by Abbott & Costello and W.C. Fields, as well as westerns — all of then focusing on scenes of physical comedy and adventure.

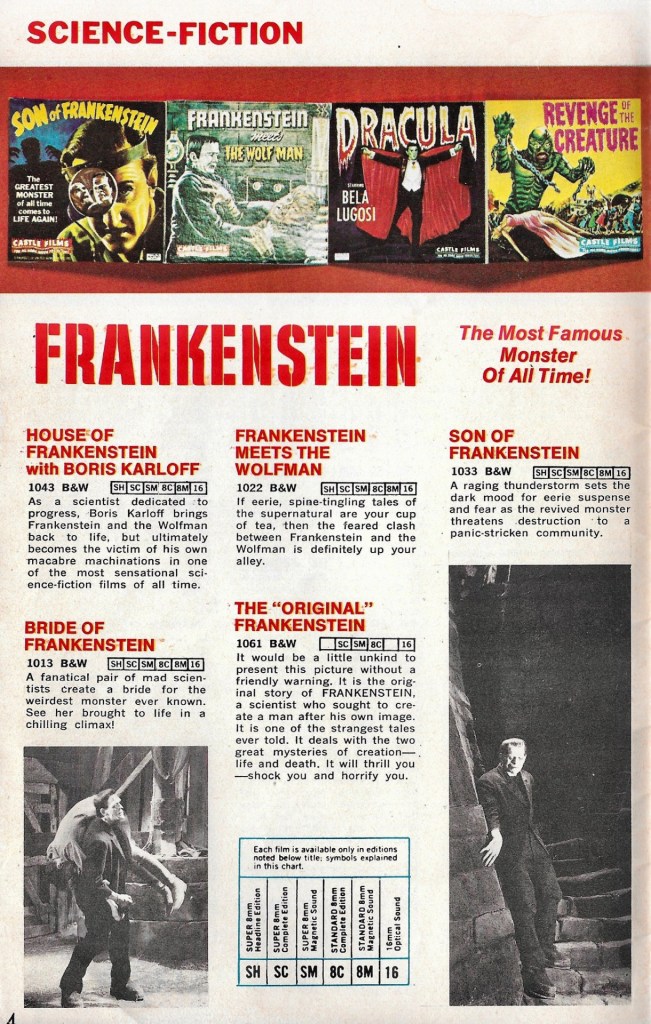

These silent mini-movies (sound versions, which used the film’s original score and dialogue, were introduced later as home projectors became equipped with sound) were offered in two formats: the “Complete Edition” of 200’, with a ten-to-twelve-minute running time, and a 50’ Headline Edition, a glorified trailer showcasing the highlights of the longer edition, running around three minutes. The footage was edited into a sort if “digest,” sometimes giving an overview of the entire film, and sometimes only focusing on a specific scene.

In 1959, Castle reached a new milestone, as the release of an abridged version of Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein tapped into the monstermania of the 1950s. By then the Universal Horror films from the ‘30s and ‘40s were undergoing a renaissance on syndicated television, and now the kids could have an actual copy — albeit a severely shortened one — to watch in their living rooms.

You found Castle Films in the camera section of your local Kresge’s or K-Mart in revolving racks similar to those used to display news-stand comic books, but most horror fans of that era will remember their first exposure to Castle’s horror films came from the back pages of Famous Monsters of Filmland. John Landis has often cited Famous Monsters and those short digests as a major influence on him; Steven Spielberg even used dogfight footage from a WWII Castle film alongside scenes he shot at an airport in one of his early shorts, Fighter Squad.

So how did these films differ from their theatrical counterparts? The Castle version of Frankenstein Meets the Wolf-Man was edited to depict the two Cockney grave-robbers invading Larry Talbot’s resting place, which leads to the climactic, castle-crumbling finale between the titular monsters. For Lugosi’s Dracula, Castle’s rendition managed to filter out much of the awkward staging found in the feature. By removing the Transylvania scenes altogether and the Renfield subplot altogether, it opens up as Dracula walks the streets of London in full evening wear. This cleaned-up, shorter version gives the film a different, more urgent life.

Castle’s The Mummy, released in 1962, was unique because it featured inter-titles from the original film, and was one of the few instances in which the full cast was credited in a Castle Film. Unlike other Universal horrors, The Mummy contained an elaborate silent scene where Karloff’s fate as Amon-Ra is staged in a fantastic pantomime. Much of the horror in the film lies in Karloff’s expressionless face, motionless dur to Jack Pierce’s rigorous makeup application. His mummification scene results in one of the spookiest Castle Films ever released.

By the 1940s, monster movie plots had worn thin and many of the sequels were nothing but filler — a loose narrative with barely enough to keep the kids in their seats until the monster would strike. They also featured sound cues re-used several times since The Bride of Frankenstein. Taking this into consideration, Castle understood how to market these films to fans: cut to the chase and include the good monster scenes. This was accomplished with careful editing. Cutting a 65-minute feature into 12 coherent minutes takes skill, and these editions aimed to highlight the excitement and thrills of the original films. Skillful economy would also be shown in the release of titles: many of the 1940s House of… films could be edited into several digests (such as Doom of Dracula, cut from House of Frankenstein). Unfortunately, and most likely due to cost-saving measures, Castle adopted an early practise of not crediting the editors responsible for trimming the films down. Castle Films: A Hobbyist’s Guide makes no mention of those involved except for company founder, Eugene Castle, who edited the films prior to the addition of the Universal catalogue.

Beyond the wonderfully edited products they offered, what really set Castle above the rest was the great box cover art. Until Castle popularized 8mm Hollywood productions, the home-movie market saw no need for exciting cover art. Along with those from competitors such as Official Films, most of the early releases had generic boxes, with the title printed on the cover flap.

The majority of the images used for Castle cover art were renditions of movie stills using primary colours that were then affixed to brightly coloured backgrounds, including the aqua-marine and pink used as a background on the background on the box for The Mummy’s Ghost. Exceptions to the rule were the nearly identical covers for Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein and The Bride of Frankenstein, the image for the latter portraying Glenn Strange as the Monster instead of Boris Karloff.

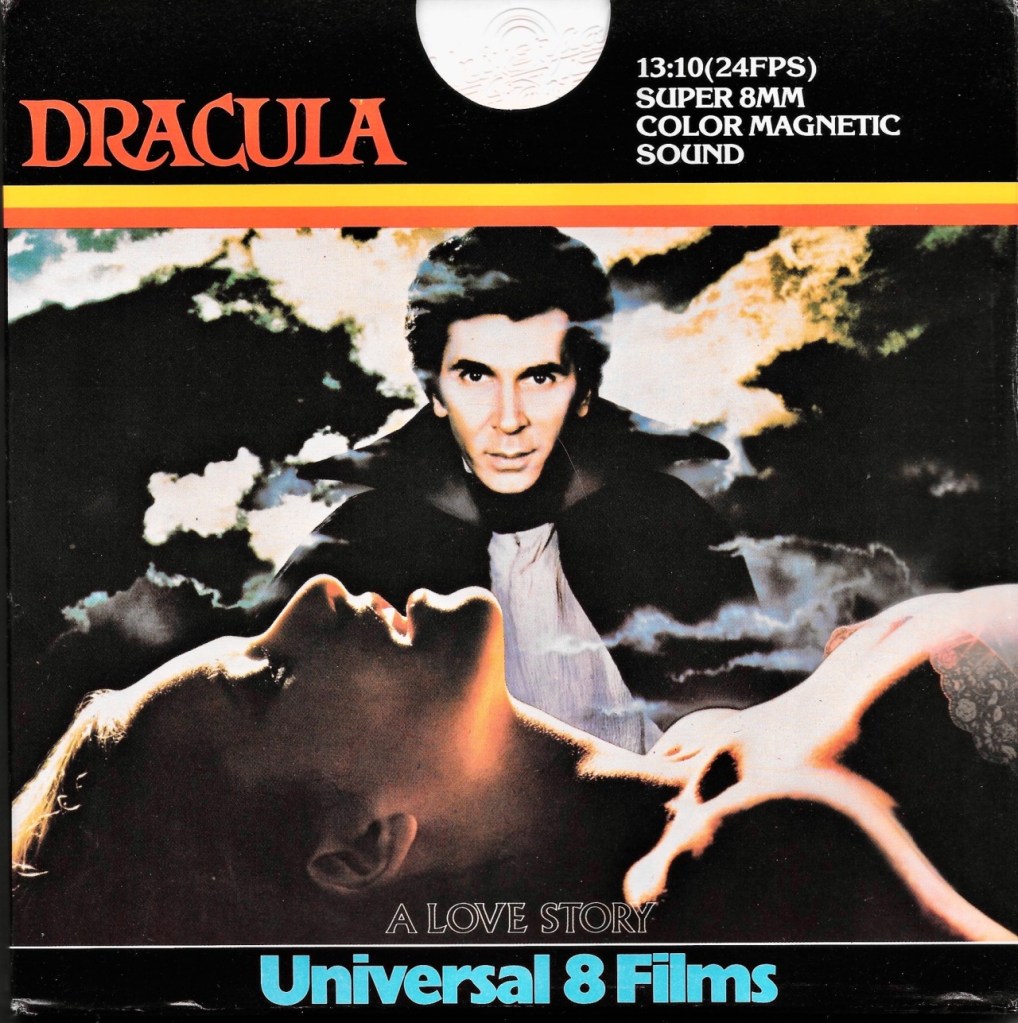

The Pulp Novelties company has released two volumes of 8mm cover art called The Monster Box. Packaged in actual reel boxes, the 25-card sets feature not only Castle’s output, but also some from Ken Films, Republic and Columbia. While celebrating them all, they acknowledge that Castle went “that extra distance to create original, well-rendered illustrations.” The sets do not feature of the covers from Castle’s successor, Universal 8, which revamped all the covers with a neon yellow background and a posterized still from the films.

Launched in April of 1977, Universal 8 Films went a little further with the post-Castle line, offering more sound editions as well as lengthier 400’ abridgements. It released an excellent digest of John Badham’s 1979 Dracula starting Frank Langella, which was prologued by an introduction from producer Walter Mirisch. The popularity and affordability of Super 8 sound projectors made it possible to use footage that would not have worked as a silent film, which is something many of Castle’s competitors didn’t get in the first place; the editors over at rival Ken Films (which distributed digests of Universal’s films) would cut together a film using only scenes of dialogue, simply because they featured the star of the movie — not very exciting when projected in your living room at your 10th birthday party.

Collecting these 8mm and Super 8 reels might seem redundant today, since there are wonderfully restored versions of the original films on DVD and Bluray. But Castle Films and their contemporaries produced a unique product of the time, worthy of the same respect their complete counterparts have earned. When DVDs became the standard home video format, many people got rid of their VHS collections, but they were simply upgrading to something better, albeit the same. The Castle digests kept some people thinking about the next time they’d see the whole thing on the late show or at the local cinema, but to most, it was a satisfying viewing experience on its own. Here’s hoping there’s some parallel universe out there where K-Mart still sells them.

This article was originally published by Rue Morgue Magazine in 2009. It has been edited and revised since publication.